Ecclesiastical Pewter

EARLY ENGLISH FLAGONS

Many of the flagons that collectors chase for their collections have survived because they were made for use in churches and when no longer needed were put away in a vestry cupboard and forgotten. If they belong to a Church of England parish these articles should not be sold without the granting of a diocesan faculty however different rules apply to other churches and inevitably ‘leakage’ occurs especially when the value is not appreciated. These flagons had two main uses, the first to hold the communion wine which was consecrated in the flagon and the chalice recharged as necessary, the second use was to hold the water needed at the font for a baptism. It is not possible to distinguish domestic from church items as no specific design was used in church. Pear shaped flagons were made in the 16th century but are seldom seen, more commonly we see the James 1 style with dome shaped lids and a knob. This style was followed by the bun lidded ‘Charles 1’ and then the ‘beefeater’, so called because of its lid shape. Many of these last two designs are still housed in churches. Other types followed such as the straight sided and spire flagons.

YORK FLAGONS

During 2017 to 2019 a member of the society researched these by visiting Churches, Museums, Cathedrals, Minster, and Church Wardens mostly in North Yorkshire around, in and beyond York as far as Teeside. In 1915 two volumes of Yorkshire Church Plate showed there were then 69 such pieces known to the author. (86 known of today) They referred to them as “St Denys type” after the flagons now in York Minster formerly at St Denis Church Walmgate. Ron F Michaelis referred to them as Acorns but did no more (as seen in the library) other than count them. John Richardson did some work on the subject and another member found information relating to 29 of them. A nice project, as there were no fakes found.

These Communion flagons were used probably from 1690 to 1790 and only in Yorkshire. The first makers recorded are a family name of Penington Pewterers in Tadcaster apparently making these 1697-1720, at least. There are variations within the few found of finial, thumbpiece, size and subtleties in shape differences.

THE PENINGTON STYLE YORK FLAGON

There are 11 known. 1 is in a museum, 10 are with the Church.

Sizes vary from 12 inches overall to over 16 inches (one supposed larger height is unknown).

This is the mark most often found (R P)

THE HARRISON STYLE

There are 68 now known of the most commonly found style of York Acorn Flagon which was mostly made by the Harrison Family of York over perhaps 3 generations from 1725 to perhaps 1788.

There were at least 5 others who made them 4 are unknown from their marks but a Richard Chambers of York marked his.

Known of in 2020 are 25 in private Collections, 25 in Museums, 15 in Churches

IH is the most commonly found makers mark.

Handles thumbpieces, finials (5 found without finials), spouts, lids and body fillets – vary.

Sizes seen are from 8 5/8 inches to 16 inches overall.

Some taken from old photos their whereabouts now are unknown.

THE EDMUND HARVEY STYLE

Working in Stockton on Tees from 1725 to 1781. Some seven only examples are known. Two are without lids (now).

1 is in a private collection, 1 is in a museum and 5 are with Churches.

Those in Churches are usually within a day’s horse ride to Stockton and back.

Size varies from 7 inches table to rim to 10 inches.

Courtesy of John Bank

PLATES

Plates were used as patens (for the communion bread) and others used for collection plates were common but as many of these did not have inscriptions it is impossible to distinguish them from domestic ones. We do occasionally find engraved alms plates from both parish and non-conformist churches dating from the late 17th century to the 19th century. From Scotland there have come dishes/chargers with clear dates and place names. Many of these were sold when the Free Church of Scotland amalgamated with the Church of Scotland in the early 20th century and surplus buildings and their contents were disposed of. The quality of these and their often accompanying chalices is high. Much prized are the alms dishes with royal medallions as a centre boss, often from London churches.

CHALICE

The third main type of church pewter is the chalice. The scottish ones are large, bucket shaped and in Scotland usually referred to as ‘communion cups’. They frequently have bold inscriptions noting the place and date. English ones are of a wide variety of designs and in the main smaller than the Scottish ones, inscriptions are rare and when present on chalices or flagons much more discrete. It is an oddity about chalices that the vast majority do not have maker’s marks although ‘hallmarks’ are seen infrequently. A rare example of a touchmarked piece is at St Cyres Church in Angus with the mark of William Eddon of London, active 1690 – 1747, there is a story there of its migration! A beautiful ‘hallmarked’ one is in the treasury at Chichester Cathedral with the marks of Robert Isles of London, working 1691 – 1735 but with a dramatic armorial added c1850. Irish chalices commonly have a thick stem and straight sided bowls.

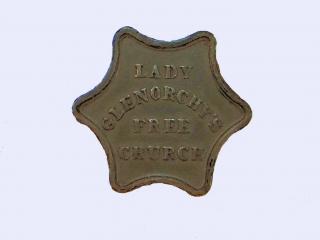

COMMUNION TOKENS

Communion tokens were first used by the Protestant churches in France in 1561, but had made their way into Scotland by the end of that century. They were given out in advance to those deemed fit to participate in a forthcoming communion. On the day, they had to give up the token before being allowed to take their place at one of the communion tables. They were used by most of the numerous Protestant denominations in Scotland. They were never used to any significant extent in England, save in Presbyterian churches with a Scottish link.

They are most often made of pewter, though examples in brass and lead exist. Most have text on both sides, though a few are plain on the back. Many have a simple border, and some also contain decorative designs. Some early examples were simply cut from flat sheet and stamped with a punch, though there are no examples of this method of manufacture in the present collection. Others were cast in a mould, often fairly crudely. Later examples were made by die stamping, and this is reflected in the quality of the impression.

They usually include either the initials or full name of the church. Most later examples have the full name (often abbreviated), so those with initials only are likely to be earlier. They often also contain the initials or name of the current Minister, a communion table number and a biblical or other religious quotation. Many are dated. The date may be the date the church was founded or the date the Minister was appointed. In either case, the token may not necessarily have been made then as further tokens with the same date may have been struck later. However, sometimes the date is in the middle of a Minister's tenure because the church decided to commission a new set of tokens, in which case the date is likely to be the date the token was made.

There are square, rectangular, round, oval and octagonal examples, and one star-shaped. They are normally 18th and 19th Century.

The Dunblane Museum has a collection of over 6000 tokens on display at the museum.

Sources: Several catalogues of communion tokens have been produced over the years, but the latest and most complete is Burzinski 1999. Unfortunately Burzinski is scarce as it was printed in a limited edition of only 250 copies. For the history of communion tokens, see L Ingleby Wood 1907 chapter XI.

PILGRIM BADGES AND CANDLESTICKS

Pilgrim badges are another field and often seen as many have been unearthed by the ‘mudlarks’ searching the Thames mud and other rivers, they date from the late 14 -16th century. Candlesticks were used in churches but due to the lack of inscriptions it is hard to distinguish between church ones and domestic ones, remarkable ones can be seen at York Minster.

See a more detailed article on Pilgrim Badges in the collecting section