The Pewterer

A pewterer would have learnt his trade from a master, almost always via an apprenticeship.

From mediaeval times the activities of the craft and trade guilds, such as that of the pewterers, were inextricably linked to the life and economy of the town or city. It was almost impossible to set up in a craft or trade in a city without becoming a freeman (or free burgess) of that city.

Admission to the freedom of the city was possible in 4 ways:

- By being the son of a free burgess.

- By marrying the widow or daughter of a free burgess.

- By serving an apprenticeship with a master who was a free burgess.

- By redemption, that is by paying a “fine” to buy the privilege.

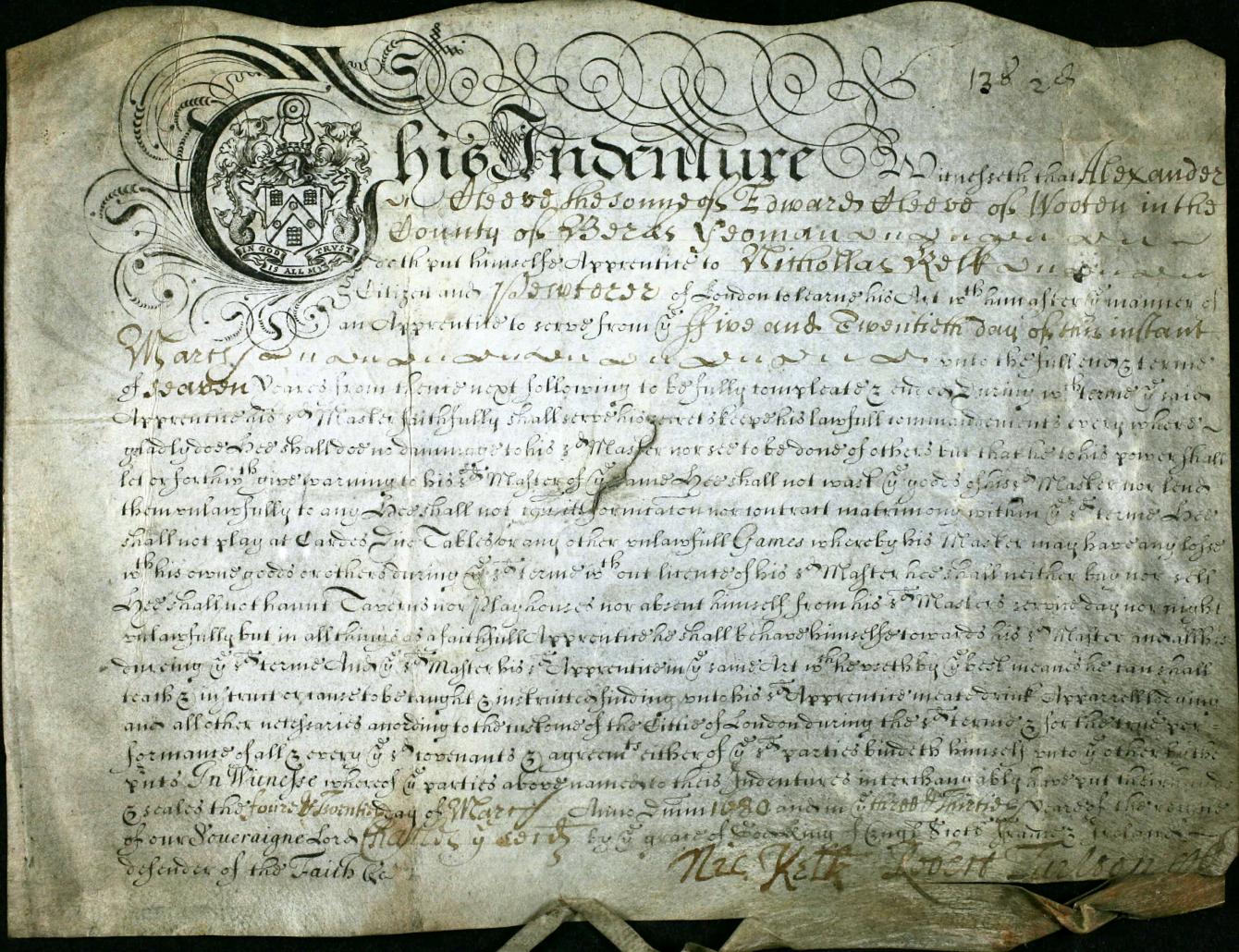

The most common of these 4 ways to freedom was by apprenticeship to a master. The apprenticeship was normally for 7 years, and boys would typically be 14 or 15 years old when they started their apprenticeship. No-one could become a free burgess until they were at least 21. The master would teach the apprentice about the “mysteries” of his craft, and he was responsible for providing food and lodgings for the apprentice who would normally live with the master and his family. For his part, the apprentice (quoting an 18th century indenture) had to “behave himself in all things, as well in words and deeds” and specifically he was “not to frequent taverns, play at dice, commit fornication, or contract matrimony”.

If his master died, the apprentice would be turned over to another master to complete his apprenticeship. But sometimes, in these circumstances, an apprentice was allowed to complete the apprenticeship whilst still working for the master’s widow who was keeping the business going. Occasionally, if it was mutually agreed, the apprentice could be turned over to another master, even though his original master was still alive.

An apprentice would usually take up his freedom shortly after successfully completing his apprenticeship. Not all apprenticeships were completed, for various reasons, but most were.

It was clearly important that the municipal authorities kept an accurate record of apprenticeships, and of those who took their freedoms. These records still exist in many towns and cities, and provide a valuable resource for the study of the trades, and commercial and business history, of the locality.

The old master/ apprentice system continued more-or-less unchanged until the mid or late 18th century. By this time the restrictions on trading in a city were starting to disappear and the value of being a freeman was starting to decline, and some apprentices did not bother to take up their freedoms after the apprenticeship was finished. However there was still some importance attached to being a freeman, and this was because only freemen were able to vote and elect Members of Parliament. This all changed with the Great Reform Act of 1832. But until then a huge rush of new freemen can be found in the records, just before the time of a parliamentary election. It is quite possible that the fees for these freedoms were being paid by one or other of the parliamentary candidates!

The 1832 Reform Act, with changes in voting qualifications, and the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, which greatly changed the constitution of boroughs and cities, saw the end of the period when having a freedom carried any practical advantage. The master/ apprentice arrangement continued but, from then on, becoming the freeman of a city was used for ceremonial purposes only.

Further reading

Guilds, Society and Economy in London 1450 – 1800. Edited by Ian Anders Gadd and Patrick Wallis. Centre for Metropolitan Studies, 2002. This contains a number of essays, including one by the late Dr Ron Homer – The Pewterers’ Company’s Country Searches and the Company’s Regulation of Prices.